The Blueberry Farm and the Kincaid Loop

Background

On December 10th, 2022, a small group of residents of the Kincaid Loop gathered at the T.B. McPherson community center in Southeast Gainesville to discuss the fate of the "blueberry farm", a parcel of land surrounding T.B. McPherson on its north, east, and south. The land, recently acquired in November 2022 represents tens of acres of land, in recent memory used as a blueberry farm, left to fallow, logged, and left to fallow again. The Calf Pond Creek flows through the land on its way to sinks of the Paynes Prairie watershed. Its immediate neighbors include Siembra Farm, T.B. McPherson, and the Lincoln Estates, Breezy Acres, and Colewood subdivisions, all majority Black.

Some threads of thought surrounding its future use include a habitat restoration space, agriculture, and housing. The Kincaid Loop has some unofficial history of being racially segregated. White, often progressive families own large tracts of land in the Loop with mind to conservation and small-scale vegetable agriculture. Black families on the Loop own houses in 1960's-era subdivisions and are often much lower income. Currently, most of the stakeholders participating in the discussion are these white landowners.

I wanted to take it upon myself to understand how the history of the region and the land could (or could not) inform its future land use. It was a much bigger project than I expected it to be, combing through stories, deeds, laws, maps, censuses, genealogies, interviews, and newspaper records to inform my own response. The clear history of the land spans a little less than two centuries, although the region's indigenous pre-colonial history spans much further than that. My hope is that we can uphold a concept of land where history is uplifted from mere palimpsest to intentional preservation where it has been preserved. This can include ecological and indigenous history, but also the stake of previous landowners, and the image of the land as it will be used and stewarded by those people yet to come. Just as importantly, such a land use must address the racial segregation on the Kincaid Loop and disparities in access to the City experienced by those who live where land has been speculated.

History

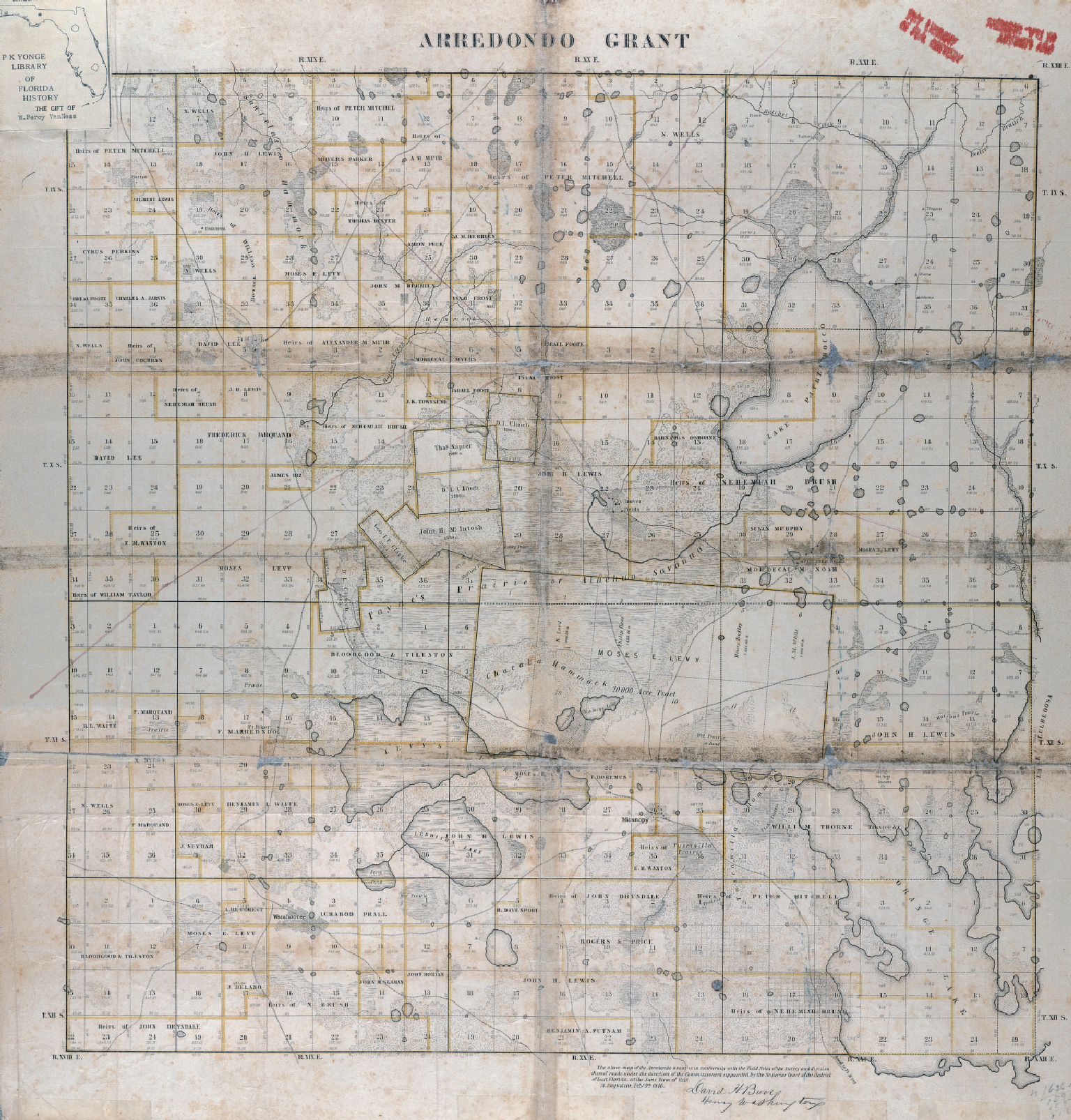

In the millenium prior to Spanish colonization, the land that is now Alachua County was inhabited by peoples of the Alachua culture, characterized by particular pottery and architectural styles. At the point of contact, the region was inhabited by the Potano tribe, related to the larger Timucua tribe by language and culture (Milanich 1994). The Potano people maintained the open grassland habitat of the region for hunting and ease of walking by controlled burning (Bushnell 1978). The traces of these are found in the Arredondo Grant map, where the northern rim of Paynes Prairie is labelled the "Alachua Savanna" (Burr n.d.).

Spanish colonists started making inroads from St. Augustine in the early-mid 16th century. Throughout the century, Spanish colonists led by Hernando de Soto decimated Potano villages either directly or indirectly through disease, establishing missions throughout what they called the Potano Province (Milanich 1995).

In the mid 1600s, on the northern rim of Paynes Prairie the Menéndez Marquéz family establishd the hacienda de la Chua (Ranch of the Sink; chua is a Timucua word for sink) (Bushnell 1978). La Chua became one of the most prosperous ranches of the region; it was attached by pirates and was one of the sites of the 1656 Timucua Rebellion (Blanton 2014). By the early 1700s, significant war and economic pressure forced the abandonment of la Chua. As the Spanish fled, bands of the newly forming Seminole tribe began resettling in the region, as inferred by the Arredondo Grant appeal case in the Supreme Court: "formerly inhabited by a tribe of Seminole Indians, but subsequently abandoned by them" (Baldwin and SCOTUS 1832).

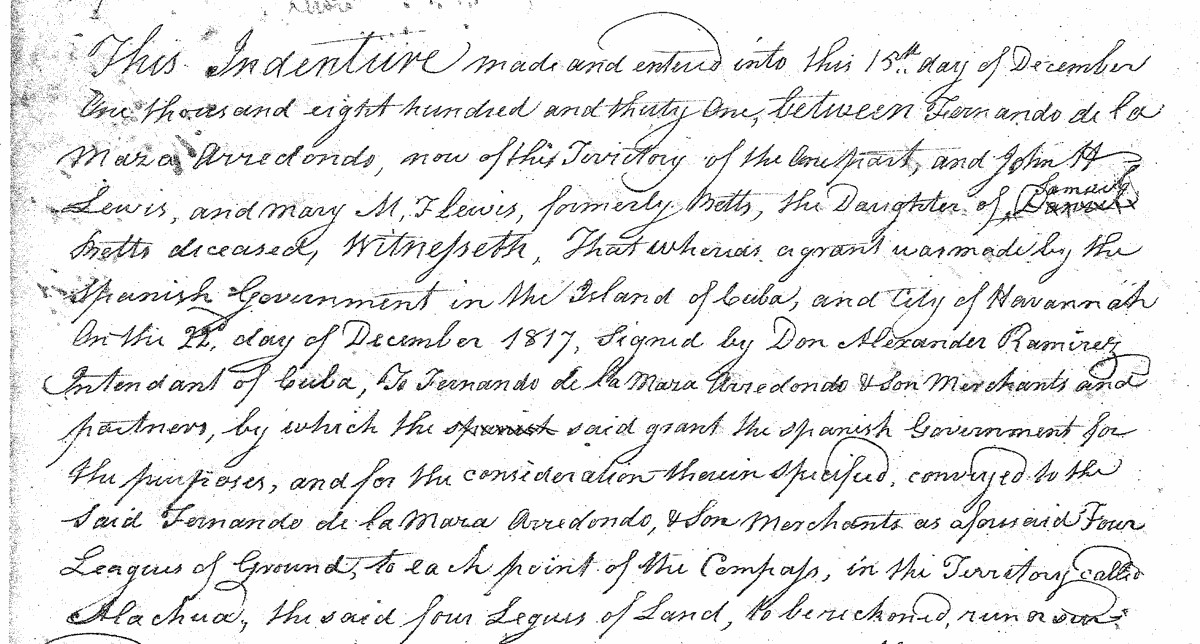

In the early 1800s, Fernando de la Maza Arredondo (1787-1840) arrived from Spain to carry out colonization work across Spanish East Florida. For his work, the Spanish king gifted Arredondo hundreds of thousands of acres of what now is Alachua County, and parts of Marion and Levy counties (Baldwin and SCOTUS 1832), including the land of the blueberry farm, Kincaid Loop, and Paynes Prairie, under the condition of settling 200 Spanish families in the region. With the cession of Florida to the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War, the validity of Arredondo's claim to the land was brought into question by the United States courts. Around the same time as the cession, the first Seminole War broke out across Florida against settlers, resulting in Seminoles driven from North Florida both out of Florida and into Central Florida.

Arredondo's claim was affirmed in the Supreme Court case US vs. Arredondo et al. (1832). Between 1819 and the mid 1830s, Arredondo sold off a lot of his claim to the land to speculators and settlers. One notable settler was Moses E. Levy, who bought claim to a lot of Paynes Prairie, Micanopy, and more with the intent of settling Jewish families (Monaco 2005). The land of the Kincaid Loop and a lot of the northern rim of Paynes Prairie was sold to John H Lewis and his wife, both white people of Madison County, Alabama (Alachua County DB A: 159). It's mostly unknown how John Lewis used the land.

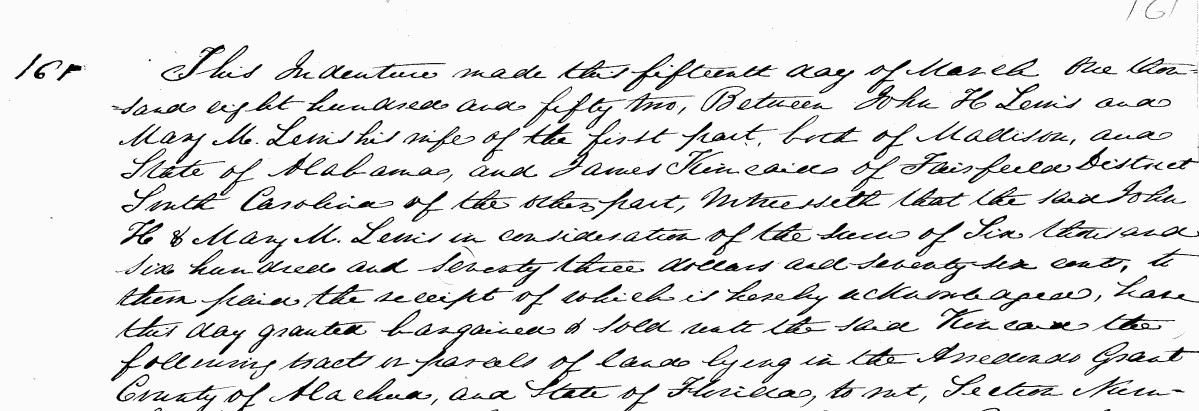

After only two decades of ownership, John Lewis sold the west half of Section 10 Township 10 Range 20 (the land of the blueberry farm) and some of the northern rim of Paynes Prairie (the east half of Section 26 T10R20, and Section 23 T10R20) to James Kincaid (1822-1896) and family, a white family from Fairfield District, South Carolina (Alachua County DB B: 161). The eastern half of Section 10, and another contingent part of the northern rim of Paynes Prairie (Section 24 T10R20, and a fraction of Section 25 T10R20) was sold to James' brother, Bolivar Kincaid. Section 15 and Section 22, the land just south of Section 10 which now form so-called Flamingo Hammock, was sold to a farmer, P.G. Snowden, in 1859 (Alachua County DB C: 325-6), who thence split it into many more smaller parcels with more owners.

According to oral history from descendants, the Kincaids were a family that originally moved down from South Carolina to farm. Along with the land around the Kincaid Loop, they acquired more land around Newberry (Section 8 T10R19) and ran a general store in Newberry. The Kincaids, Stringfellows, Warners, LaFontissees, and Feibers are all intertwined either through business or marriage. The third generation Kincaids were witness to the Newberry Six lynchings (Cofrin 1994).

Throughout their ownership of Section 10 and the northern rim, the Kincaids used the land mostly agriculturally, but it's unknown for what type of agriculture (Cofrin 1994). The land passed through the Kincaids; James Kincaid Sr. passed on in 1896 without a will, leaving his land to his children. The land was formally passed to Mary "Mamie" Kincaid Warner in 1927 (Alachua County DB 149, 201-2). In 1931, Mamie and John Kincaid sold their Paynes Prairie tracts to the Camp family of Ocala (Alachua County DB 131: 338). The Camp family acquired much of Paynes Prairie and the northern rim, interested in "generating electricity by plugging the sink and harnassing (sic) the overflow". The Camps created a complex system of drainages that severely harmed the hydrology of the Prairie (Belton 2015). Power-of-attorney was given from Marion and Louise Kincaid to Bolivar Kincaid Jr. in 1937 (Alachua County DIG 1928, 199).

Upon Mamie's passing in 1956, Bolivar Kincaid Jr. assumed control of the land and sold the northern tract (W 1/2 of Section 10) where the blueberry farm was to Hugh C. Edwards (Alachua County DIGee 1928: 209). Hugh C. Edwards was a prominent developer in Gainesville, creating many mid-century suburban subdivisions including Carol Estates, Libby Heights, Debra Heights, Woodland Terrace, Michigan Heights (now Northeast Neighbors), Rose Wood and Pine Woods (Modern Gainesville). Hugh C. Edwards, however, did not develop Section 10 and instead sold it to Dave Emmer of the Emmers, a historic and current major player in Gainesville's real estate scene. The Emmers developed the northwestern 1/4 of Section 10 in what is now Lincoln Estates. They transferred the southwestern 1/4 of Section 10 into a shell corporation titled "Florida Blueberries Inc." and the land was retained as agricultural instead of being rezoned as residential. In 1994, the land was sold to Thomas C Dorn, who ran Dorn Liquors and Wine Warehouse in the Millhopper area (Alachua County DB 1994: 279). The blueberry farm continued to exist in fallow but began becoming overgrown with laurel oaks. In late 2020, the entirety of the parcel was logged and cleared with the intention of replanting a slash pine plantation, leading to outcry from neighbors over damage to habitat for gopher tortoises and damage to the Calf Pond Creek watershed (Hernandez 2020).

With Thomas Dorn's passing in 2022, the core land of the blueberry farm, through which Calf Pond Creek runs was sold to Daniel Kahn of Tallahassee (Alachua County DB 5036: 340), director of Florida Restorative Justice Association and with long term ties in Gainesville. Other side parcels abutting the south end of the farm have been purchased variously by Robert Terell of the Repurpose Project, Flairy Farm (James Longanecker, and Jen Speedy of Siembra Farm), and Cody Galligan of Siembra Farm.

Imagery

To aid in visualizing changes in the Kincaid Loop, I created an ArcGIS app using USDA and FDOT aerial imagery. Below you can pan through slides and note the changes between 1949 and 2017 in the site.

The future

The land of the Kincaid Loop went from a Potano-maintained hunting ground, to Spanish colonization for cattle, to Anglo white farming settlers, to its current constellated use as farmland and conservation by mostly white stakeholders, and housing for mostly Black families. The land connects to a larger pattern of settler colonialism, from its seizure by the Spanish for resource extraction to its valuation by speculators for Anglo settlers, including developers that ran a profit by creating industrially produced subdivisions. It is unknown whether there is a larger Black history before the 1950s in the area, for example, whether James Kincaid or John Lewis owned slaves prior to emancipation or if there were free Black settlers in the area.

Since colonization, the blueberry farm and surrounding primary use has been agriculture, whether for cattle or blueberries. Nearby acreage is used as well for agriculture and for housing. If the tract of land goes the way of development in Florida, even if it is initially replanned as agriculture, it's likely to not remain that way due to increasing pressure for housing and the lack of perceived market value in maintaining agricultural land. Housing is a much higher, more profitable land use, so without community investment in the land (i.e. it remains with one or few private stakeholders), it is likely to be bought out for suburban housing development once the private stakeholders see it more as a liability to maintain.

To break the pattern, I believe that the planning of the process must include as wide as stakeholders as possible, not only the white landowners of the area as it currently is, but also Black stakeholders in imagining a land use that people want to invest in. More importantly, the land ownership governance of the site should reflect that. Currently the land is held in constellation by multiple private stakeholders. Instead, reinvesting the property in some type of community organization e.g. a land trust or a cooperative, reflects a resilient governance that can withstand market pressure.

In any and every case, the form that the property takes should reflect a planning process that allows diverse political control, instead of reflecting a covert privilege of class and race. If it does end up being that housing is the preferred use, that should be understood. If it does end up that parks are the desired use, so be it. Regardless of the use, the use should be well planned and thought out through affirmative inclusion in the process. The lack of this inclusion will only propagate the cycle of development by speculation in the region.

Sources

Alachua County, Florida, Chancery Order Book A; Deed Index Grantee HIJK from 1928: 209; Deed Index Grantor HIJK from 1928: 199, 209; Deed Books A: 159; B: 161; C: 325-6; 131: 338; 149: 201-2; 1994: 279; 5036: 340.

Baldwin, H. & Supreme Court Of The United States. (1832) U.S. Reports: United States v. Arredondo and others, 31 U.S. 6 Pet. 691. [Periodical] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep031691/.

Belton, K. (2015). Paynes Prairie. Pepine Realty. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.pepinerealty.com/blog/paynes-prairie/

Blanton, J. B. (2014). The Role of Cattle Ranching in the 1656 Timucuan Rebellion: A Struggle for Land, Labor, and Chiefly Power. The Florida Historical Quarterly, 92(4), 667–684. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43488429

Burr, D. H. (n.d.). Arredondo Grant, 1846. University of Florida Digital Collections. map. Retrieved 2022, from http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF90000020/00001.

Bushnell, A. (1978). The Menéndez Marquéz Cattle Barony at La Chua and the Determinants of Economic Expansion in Seventeenth-Century Florida. The Florida Historical Quarterly, 56(4), 407–431. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30150328

Cofrin, M. A. (1994). Interview with Katherine Kincaid Feiber. other. Retrieved 2022, from https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/MH00001754/00001/citation.

Florida Department of Transportation. (1964, 1994, 2008, 2017). FDOT Aerial Imagery. Aerial Photo Lookup System. map. Retrieved 2022, from https://fdotewp1.dot.state.fl.us/AerialPhotoLookUpSystem/.

Hernandez, M. (2020, September 28). Blueberry Farm-to-pine farm move rattles neighbors. Gainesville Sun. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.gainesville.com/story/news/local/2020/09/28/blueberry-farm-pine-farm-move-rattles-neighbors-who-say-gopher-tortoises-threatened/3562918001/

Milanich, J. T. (1994). In Archaeology of precolumbian Florida (pp. 330–340). essay, University Press of Florida.

Milanich, J. T. (1995). In Florida Indians and the invasion from Europe (pp. 90–91). essay, University Press of Florida.

Modern Gainesville. (2022, July 11). Hugh Edwards, Builder and Developer. Modern Gainesville. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://moderngainesville.com/hugh-edwards-builder-and-developer-gainesville-florida/

Monaco, C. S. (2005). Moses Levy of Florida: Jewish utopian and antebellum reformer. Louisiana State University Press.

US Department of Agriculture. (1949). Aerial Photographs Of Alachua County - Flight 2F (1949). UF Digital Collections. UF George A Smathers Libraries. Retrieved 2022, from https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00071726/00015/citation.